We were educated pre-colonisation

By Ninot Aziz

By Ninot Aziz

Sometime this month, we have seen trending on social media a list of schools touted as the earliest education institutions established in, at the time, Tanah Melayu or Malaya, at the beginning of the 19th century.

Like all things, there is a disconcerting idea that civilisation, culture and coming of age for Malaysia was only possible post British colonial times.

It is quite surreal to see Malaysians support the idea, in perplexing jubilation that education in Malaysia only took place after the British marched into our corridors, built schools and “bestowed” education into our lives.

This could be the most damaging untruth we allow into our history. Our education definitely did not begin with the British, and our education system, like our laws and commerce, did not exist only upon Western indoctrination. We had our own education and knowledge systems we should be proud of which have existed in our land pre-British rule.

Not one to dispute the benefits of British education, this article seeks to dispel the notion that Tanah Melayu did not have an education system worthy of mention before the Penang Free School was established.

Informal education of values, character and knowledge inherited from generation to generation is crucial to nation-building. In this sense, this is how education begins in a Malay household, with Quran studies starting early in life. We can attest to the importance of early informal education where we see Finland — touted as having among the best education systems in the world — only starts formal education at seven years of age.

Since the 7th century, hundreds of years before the British, there were many sekolah pondok or funduq (ie. boarding schools) and madrasah (a term to describe any type of educational institution, secular or religious) established across the Malay Archipelago.

It became a prominent mainstay in Tanah Melayu in the 15th century after the Melaka Sultanate was established. Many Malays who attended sekolah pondok or madrasah then were already travelling to further their education in known centres of learning such as Makkah and Cairo, before later coming back to establish their own sekolah pondok or madrasah.

Thanks to the British penchant for “good” record keeping, the oldest recorded sekolah pondok post British rule was said to be founded in Pulau Chondong circa 1820s by Tuan Haji Samad Abdullah who hailed from Patani. Conveniently, it put the Penang Free School established by the British in 1816 as the oldest recorded school in modern Malaya, exalting them as the bringer of education in this country while blatantly ignoring all other sekolah pondok and madrasah that existed before their rule across Tanah Melayu.

In William Shellabear’s edition of Sejarah Melayu, he said that after Melaka was established as an Islamic polity, between the 15th and 17th centuries, the teachings of Islam spearheaded education in the community where the Malays studied with renown scholars.

Illiteracy was eradicated, and the Jawi script was used after centuries of usage of pallavi and rencong scripts.

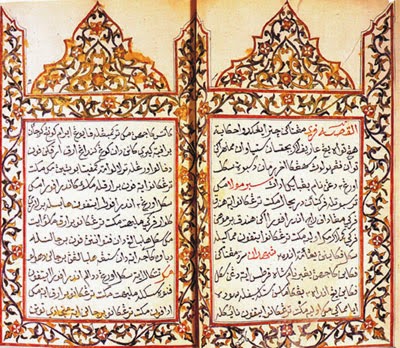

It was through this Jawi script that the Malays established over 10,000 manuscripts which are now studied in over 60 countries in more than 150 museums and libraries, offering a wide variety of subjects including history, law, medicine, weaponry, literature, starcharting, maritime navigation, literature and cultural pursuits like music and wayang kulit.

Written since the 15th century, if not earlier, the Malay Manuscripts are proof that various schools of thought, the result of a clear path of learning, existed for centuries in Tanah Melayu before the British era.

It cannot be denied that Islam brought enlightenment through the Jawi script where all households learned the Quran, and thus the Jawi script. Homeschooling, sekolah pondok and madrasah as well as silat training ensured a continuous system of learning.

In addition, in the Malay world there was a strong tradition of apprenticeship which ensured a continuous expansion of knowledge in metallurgy, woodworks, cannon/weaponry, ship building and Malay architecture (the marvel of the world with its interlocking technics and intricate pasak that did not need nails, which had disruptive corrosive properties).

The preservation of such collective skills and knowledge is crucial for the survival of the corpus of our heritage and wisdom.

Scholars like Tun Perak, Tun Sri Lanang , Raja Ali and more are proof that there was a healthy workable system of learning in Malay society.

In fact when the Tang Dynasty monk and world traveller, I Tsing arrived in the Malay World in the 7th century, namely Palembang and Kedah, he was so impressed by the schools in the area that he recommended for all scholars to spend six months studying in Srivijaya.

In 687 AD, he stopped in the kingdom of Srivijaya on his way back to Chang’an. At that time, Palembang was a centre of Buddhism where foreign scholars gathered, and I Tsing stayed there for two years to translate original Sanskrit Buddhist scriptures into Chinese.

This scholarly tradition established in as early as the 7th century, would surely be the modus operandi adopted throughout the Malay World.

This goes to show that irrespective of the religion that they professed, the Malay World had international-class education system before any European learned how to sail to the Far East.

Through the sekolah pondok and madrasah as well as the recording of knowledge in manuscripts, education in the Malay World expanded beyond our borders to reach its pinnacle in the 19th century to include tertiary education that attracted students from all over the world to learn from us.

We continue this journey to provide the best education to all — a balance of the spiritual, science and skills needed to face a new world.

There is nothing wrong in being an anglophile, but let’s not bury our own heritage and history in the process. Nst

The writer is an award-winning Malaysian author, writer and poet, specialising in Malay Hikayat and Asian legends.

You must be logged in to post a comment.